OFF THE SHELF

Rob Dietz (M.S. environmental science and engineering '00), et al, "Enough is Enough: Building a Sustainable Economy in a World of Finite Resources," sustainability, economics, Berrett-Koehler.

Newton Lee (computer science '83, M.S. '85), "Facebook Nation: Total Information Awareness," social media privacy and ethical issues, Springer.

Sean McGowan (political science '98, M.Ed. curiculum and instruction '99), "Future Glory: Walking in the Power of Your God-Given Destiny," Christianity, West Bow Press.

Joe Peta (accounting '88), "Trading Bases: A Story About Wall Street, Gambling and Baseball (Not Necessarily in That Order)," risk analysis and baseball, Dutton.

Andrew Smiler (psychology '90, mathematics '93), "Challenging Casanova: Beyond the Stereotype of the Promiscuous Young Male," human sexuality and adolescent psychology, Jossey-Bass.

Chikako Takeshita (science and technology studies M.S. '00, Ph.D. '04), "The Global Biopolitics of the IUD: How Science Constructs Contraceptive Users and Women's Bodies," women's reproductive rights, The MIT Press.

Shuvom Ghose (aerospace engineering '00), "Infinity Squad," science fiction, Libboo.

Charles T. "Tom" Tate II (marketing management '75), "Rift Weavers, A Novel in Parts, Part One: Finn Stockton," science fiction/fantasy/adventure, CreateSpace.

Rosemary Blieszner, Alumni Distinguished Professor in the Department of Human Development, et al, editor, "Handbook of Families and Aging (second edition)," aging, elder care, Praeger.

Rosemary Blieszner, Alumni Distinguished Professor in the Department of Human Development, et al, "Spiritual Resiliency and Aging: Hope, Relationality, and the Creative Self," aging, Baywood Publishing Company.

George J. Flick Jr., University Distinguished Professor Emeritus, Department of Food Science and Technology, et al, edited by Linda Ankenman Granata, research associate, Department of Food Science and Technology, "The Seafood Industry: Species, Products, Processing, and Safety," second edition, critical, Wiley-Blackwell.

Betsy Tice White, "A Patriotic Man," novel, historic fiction, WWI, Virginia Tech history, Big Elm Books.

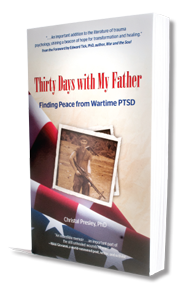

Christal Presley (English '99, M.A. English education '00), has published a memoir, "Thirty Days with My Father: Finding Peace from Wartime PTSD," in which she recounts 30 days of interviews with her father, a Vietnam War veteran.

Presley founded United Children of Veterans, a website that provides resources about PTSD to children of war veterans. The native of Honaker, Va., now lives in Atlanta, Ga., where she is an instructional mentor teacher for Atlanta Public Schools. She received her Ph.D. in education from Capella University in 2009. She is a former intern at Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill and spent seven years teaching middle and high school English in Chatham and Danville, Va.

In her memoir, Presley attempts to understand her father, his PTSD, and her own lifetime of vicarious traumas. What emerges is a harrowing portrait of the past's ability to haunt the present.Below is an excerpt, reprinted with the author's permission:

I was 6 when my father went to the [Veterans Affairs] hospital for the first time because he was so emotionally disturbed and his hands shook so badly that he knew he shouldn't go on working and that he needed to qualify for disability insurance. That's when he was finally diagnosed with PTSD, but it would take six years before he was approved for full disability. Meanwhile, he just kept on working.

To me, "posttraumatic stress disorder" was just a bunch of words. All I knew was that it had something to do with my dad's brain and he seemed to be going crazy. And I knew it was bad because my mom told me that if anyone found out how sick he was, they'd come and take him away forever, and they'd take me away too, and she couldn't live like that. If he had to be that sick, I wanted him to have something everybody could understand. So I picked brain cancer.

I envisioned a map of the human brain like I had seen on television.

"Here is a normal brain," a doctor in a white lab coat would say solemnly. He would use a pointer to show his audience the parts of the brain displayed on a screen. Each one would light up in a different color as he talked about it.

"Now, here is your father's brain," the same doctor would say, shaking his head, as my father's brain appeared on the screen. This one didn't look like the other brain. The doctor could not point out the individual parts. Everything was a jumble of mush and sharp wires all clumped together.

"Nothing we can do about this one," he'd say, and move on to the next.

Did my brain look like everyone else's—or was I a freak too? I wondered.

I was not normal. That was for sure.